I found Dreda Say Mitchell’s house on a tree-lined street in Walthamstow, bursting with leaves in the early summer. Its emerald green front door swung open to reveal her inimitable welcoming smile. Dreda is a writer of award-winning crime novels, the latest of which, Say Her Name, kept me guessing until the finish with its ingenious plot. But she has also worked for 25 years as a teacher, with a special focus on raising the educational achievement of children from minority-ethnic and working-class backgrounds. In 2020 Dreda received an MBE for her work mentoring and teaching creative writing in prisons.

Dreda showed me around the house while her partner, Tony, arranged the parking permit. She talked me through a wall of family photographs, some of them in black and white and dating from the 1950s. There were parents, uncles and aunts, all wedded in Bethnal Green. With her warm, extroverted character, I could see why young people have found a valuable role model in Dreda.

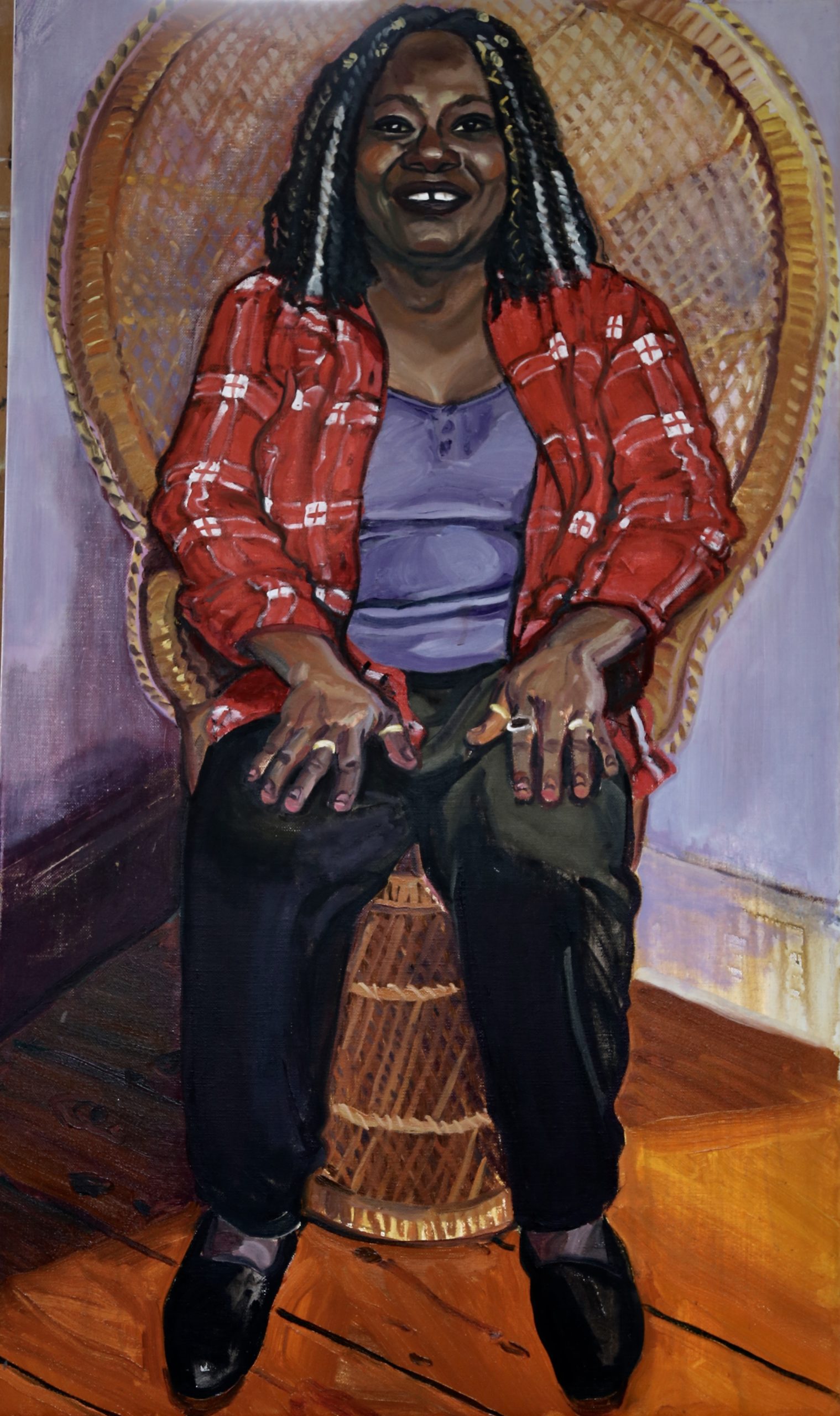

For the sitting, she chose to sit in a wicker peacock chair that has pride of place in the corner of the dining area. She had bought this treasured item as a young student and carried it home by herself. It struck me as very paintable. I needed more light on her face so I asked for a lamp, which Tony (or Tone as she calls him) duly brought in. During the drawing we kept up a steady stream of conversation about this and that, which I occasionally interrupted to remind Dreda to keep her hands still.

I sensed a wonderful partnership between Dreda and Tony, both personally and professionally (Tony has co-authored several books with her under a pseudonym). A few minutes into the drawing process Dreda called out: “Tone! Come and take a picture for my readers, they’re going to love this.” Then, after seeing the picture: “No! You take terrible pictures Tone! I look like a Buddha. Take another one!” This happened several times during the sitting, Tony always obliging when called down from upstairs.

I loved Dreda’s choice of purple T-shirt and red plaid shirt, and her hair creatively braided with silver and gold strands. The background wall was lilac, a lighter hue of Dreda’s T-shirt. She mentioned a few times that the recent lockdowns had added to the rolls of her stomach, which made me a little worried about painting this feature of her appearance. Representing an aspect of someone that they do not like is an awkward part of portraiture, especially if you lack the confidence that some painters have about the transcendent importance of their work.

Thankfully I couldn’t ask for a more authentic sitter than Dreda. As I drove home I reflected on the project’s progress and thought to myself, I am meeting wonderful people.

By November, Dreda’s portrait had already gone through several stages, with a lot of sanding down and starting again. I was finding the background troublesome. I had tried burgundy, but that was too dark and seemed to invade the foreground, since the value was similar to Dreda’s trousers. Sanding it down had pushed it back a little, but it wasn’t working. Next I tried cobalt violet, but I wasn’t sure about that either. I felt like there was too much colour in the painting.

The wicker chair was a challenge too, though after several phases of painting and sanding I stumbled on a solution of sorts. I found the sanded textures of the canvas seductive, as the visible weave of the linen added depth to the pattern of the chair. It gave the colours a faded softness that I thought worked well.

But the most difficult part of the portrait was the facial expression. I was struggling to paint Dreda with a serious look, since this just wasn’t how I remembered her. My son occasionally gives me feedback on works in progress, and he suggested the face looked overworked. Dreda had postponed our second sitting to the New Year, but I was feeling impatient so I decided to change tack. Using one of my photo references, I tried to capture her distinctive laughing expression.

This turned out to be a kind of blessing in disguise, since photography is better suited to representing a fleeting reaction like laughter. The advantage of painting from life is discovering an unguarded expression that emerges in the course of a sitting, but this process is antithetical to more transient emotions. Painting laughter is always fraught, as failure to capture the vitality of the emotion can result in a stilted expression. In this case though, I felt laughter was crucial to representing Dreda’s character.

I found it very useful to study other artists’ efforts at this particular challenge. I turned to the portraits of the Dutch Golden Age: Laughing Man by Rembrandt, and Laughing Boy by that master of laughter, Frans Hals. But my favourite portrait in this respect is Richard Gerstl’s Self Portrait, Laughing from 1907, a moving and somewhat eerie painting in light of Gerstl’s suicide just a year later, at the tender age of 25.

In the end, I felt these references and my own photographs gave me what I needed to finish the painting, so I cancelled the second sitting. The only drawback was missing out on another round of Dreda’s sparkling company.